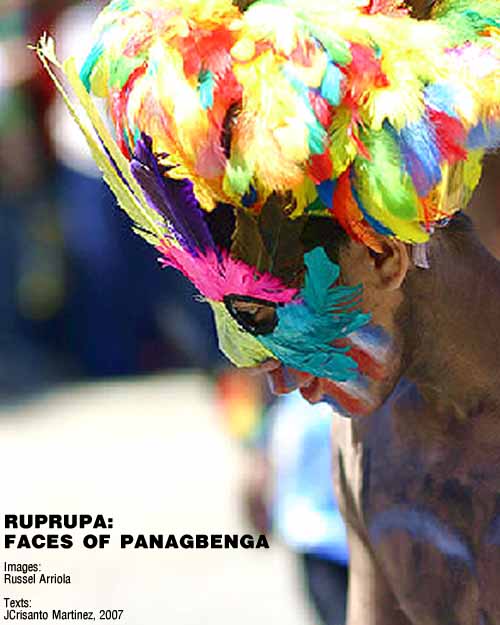

RUPRUPA:

FACES OF PANAGBENGA

The circumstances prior to the creation of a flower festival in Baguio City were appalling. No one could ever forget the wake-up call nature unleashed on the day of July 16, 1990. The killer temblor left behind massive devastation and countless deaths. As the face of Baguio City was scarred by the wreckage of life and property, a more perceptible scar left an indelible imprint in the hearts and souls of its citizens. Simultaneous with the seemingly endless aftershocks was the shock to find oneself amidst the long lines to procure food and water, with no means of power and communications, to leave in a tent exposed to the cold evenings and the uncertain days, or even just to bury one’s death. Everyone was in a state of metaphoric disfigurement.

Yet despite of it all and as things should be, life moved on for Baguio City. Amidst the rubbles, even in the sanctuaries of the dead, under the still aching pangs of fear and pain, amidst the extensive dislocation of local economy and personal well-being, the call to rise up and to continue to live life may well be unuttered but it’s the only way.

Still, there is another call to stand up and take another stride. For much as the destruction and desolation may seem the face of the Baguio City landscape started to reemerge. The flower buds appeared. It was a season to bloom. Again.

~ o ~

Panagbenga. A Kankanaey term for “a season of blooming. It is also known as the Baguio Flower Festival, in deference to the beautiful flowers the city is famous for as well as a celebration of Baguio's successful rise from shambles.

The birth of the tradition began in 1995. Atty. Damaso Bangaoet,Jr. who was then managing director of the John Hay Poro Point Development Corp. (JPDC) expounded to the JPDC the idea of holding a flower festival in Baguio City. There was immediate approval from the board which was led by Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) Chairman Victor Lim and JPDC President Rogelio Singson. The festival was set to be held every February. The idea of the festival was presented to various sectors of the community. The response was a fusion of zealousness and urgency.

The intended festival must reflect the history, traditions and values of Baguio City and the Cordilleras. Thus in October 1995, the Baguio Flower festival acquired a face. Trisha Tabangin, a student from Baguio City National High School, created an artwork that highlighted a spray of sunflowers and submitted it to the annual Camp John Hay art contest. With Ben Cabrera (now National Artist for Visual Arts) leading a panel of judges, Tabangin’s artwork was handpicked as the official logo of the festival. Shortly thereafter, Prof. Macario Fronda, band master of the St. Louis University, composed the festival hymn which was infused with the rhythm and movements of the Bendian dance, an Ibaloi dance of celebration. The circular movements of the Bendian dance verbalize the unity and harmony of the tribe; it was reflective of the coming together of the various sectors of the community to bring the BFF to life. It was in 1996 that the Baguio Flower Festival acquired a local name. Ike Picpican, an archivist and curator of the Saint Louis University Museum, came up with the Kankanaey term which denotes "a season of blossoming, a time for flowering."

Panagbenga. Let a thousand flowers bloom.

~ o ~

The annual staging of the Panagbenga has become a very much anticipated event. Thru the years, it has grown and has evolved. It has blossomed from a spectacle to be being spectacular.

The Baguio Flower Festival has become the Northern Philippines’ most sought after performance and installation art show staged more than 4,500 feet above sea level. Its massive theatrical expanse covers most of the city proper main arteries and byways with Session Road as the central arena. It exhibits a colossal pageantry of Cordillera art, customs and traditions.

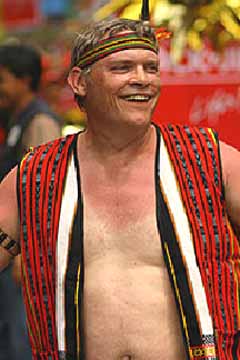

Not only is the whole local community a participant in the spectacle but people from other localities outside of Baguio City as well. Drones of denizens conduct an annual voyage to be in this place at this particular time of the year. They take part in what could be is seen as a massive performance art of street dancing along the main thoroughfares. Clad in costumes inspired by the blossoms yet reflective of the ethnicity and way of life in the Cordilleras. The main streets of Baguio City then transcend to become the center stage for what is probably the most unique exhibit of installation art. Floats parade, decked with flora, seemingly sculpted, painstakingly installed. And all throughout this vast performance/installation arts presentation, the sound of the native Cordillera musical instruments resonate. The traditional Cordillera beat that mirrors the essence of unity and accord echoes to the farthest crevice of the Baguio City landscape. It sinks deep, in the hearts and souls of every Cordilleran and the citizens of Baguio City, with its persistent call to rise up and move on, to bloom and prosper.

~ o ~

Ruprupa. In the midst of the faces of Panagbenga are the blossoms for which the festivities stand for. They are the divas in this unique gathering of talents. Each blossom is a participant in the staging of this exceptional pageantry.

Where in the face of every man, woman and child replicates a blossom; where in the hearts and souls of every Baguio citizen the sprouts the gaiety of simple life; where in every Cordilleran, the culture and tradition flourishes.

Panagbenga. Let a thousand flowers bloom a million fold.

Images:

Russel Arriola

Texts:

JCrisanto Martinez, 2007

FACES OF PANAGBENGA

The circumstances prior to the creation of a flower festival in Baguio City were appalling. No one could ever forget the wake-up call nature unleashed on the day of July 16, 1990. The killer temblor left behind massive devastation and countless deaths. As the face of Baguio City was scarred by the wreckage of life and property, a more perceptible scar left an indelible imprint in the hearts and souls of its citizens. Simultaneous with the seemingly endless aftershocks was the shock to find oneself amidst the long lines to procure food and water, with no means of power and communications, to leave in a tent exposed to the cold evenings and the uncertain days, or even just to bury one’s death. Everyone was in a state of metaphoric disfigurement.

Yet despite of it all and as things should be, life moved on for Baguio City. Amidst the rubbles, even in the sanctuaries of the dead, under the still aching pangs of fear and pain, amidst the extensive dislocation of local economy and personal well-being, the call to rise up and to continue to live life may well be unuttered but it’s the only way.

Still, there is another call to stand up and take another stride. For much as the destruction and desolation may seem the face of the Baguio City landscape started to reemerge. The flower buds appeared. It was a season to bloom. Again.

~ o ~

Panagbenga. A Kankanaey term for “a season of blooming. It is also known as the Baguio Flower Festival, in deference to the beautiful flowers the city is famous for as well as a celebration of Baguio's successful rise from shambles.

The birth of the tradition began in 1995. Atty. Damaso Bangaoet,Jr. who was then managing director of the John Hay Poro Point Development Corp. (JPDC) expounded to the JPDC the idea of holding a flower festival in Baguio City. There was immediate approval from the board which was led by Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) Chairman Victor Lim and JPDC President Rogelio Singson. The festival was set to be held every February. The idea of the festival was presented to various sectors of the community. The response was a fusion of zealousness and urgency.

The intended festival must reflect the history, traditions and values of Baguio City and the Cordilleras. Thus in October 1995, the Baguio Flower festival acquired a face. Trisha Tabangin, a student from Baguio City National High School, created an artwork that highlighted a spray of sunflowers and submitted it to the annual Camp John Hay art contest. With Ben Cabrera (now National Artist for Visual Arts) leading a panel of judges, Tabangin’s artwork was handpicked as the official logo of the festival. Shortly thereafter, Prof. Macario Fronda, band master of the St. Louis University, composed the festival hymn which was infused with the rhythm and movements of the Bendian dance, an Ibaloi dance of celebration. The circular movements of the Bendian dance verbalize the unity and harmony of the tribe; it was reflective of the coming together of the various sectors of the community to bring the BFF to life. It was in 1996 that the Baguio Flower Festival acquired a local name. Ike Picpican, an archivist and curator of the Saint Louis University Museum, came up with the Kankanaey term which denotes "a season of blossoming, a time for flowering."

Panagbenga. Let a thousand flowers bloom.

~ o ~

The annual staging of the Panagbenga has become a very much anticipated event. Thru the years, it has grown and has evolved. It has blossomed from a spectacle to be being spectacular.

The Baguio Flower Festival has become the Northern Philippines’ most sought after performance and installation art show staged more than 4,500 feet above sea level. Its massive theatrical expanse covers most of the city proper main arteries and byways with Session Road as the central arena. It exhibits a colossal pageantry of Cordillera art, customs and traditions.

Not only is the whole local community a participant in the spectacle but people from other localities outside of Baguio City as well. Drones of denizens conduct an annual voyage to be in this place at this particular time of the year. They take part in what could be is seen as a massive performance art of street dancing along the main thoroughfares. Clad in costumes inspired by the blossoms yet reflective of the ethnicity and way of life in the Cordilleras. The main streets of Baguio City then transcend to become the center stage for what is probably the most unique exhibit of installation art. Floats parade, decked with flora, seemingly sculpted, painstakingly installed. And all throughout this vast performance/installation arts presentation, the sound of the native Cordillera musical instruments resonate. The traditional Cordillera beat that mirrors the essence of unity and accord echoes to the farthest crevice of the Baguio City landscape. It sinks deep, in the hearts and souls of every Cordilleran and the citizens of Baguio City, with its persistent call to rise up and move on, to bloom and prosper.

~ o ~

Ruprupa. In the midst of the faces of Panagbenga are the blossoms for which the festivities stand for. They are the divas in this unique gathering of talents. Each blossom is a participant in the staging of this exceptional pageantry.

Where in the face of every man, woman and child replicates a blossom; where in the hearts and souls of every Baguio citizen the sprouts the gaiety of simple life; where in every Cordilleran, the culture and tradition flourishes.

Panagbenga. Let a thousand flowers bloom a million fold.

Images:

Russel Arriola

Texts:

JCrisanto Martinez, 2007